KEYWORDS INTRODUCTION

Most of us exist within language the way that a fish exists within water, which is to say that we are generally not aware that we exist within it at all. Language, for most of us, is co-terminous with thought. For this reason the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein asserted, in his most famous text,

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.

Occasionally, however, something may happen that we struggle to put into words. Something for which our everyday words seem inadequate. This could be because, in the face of an experience, our ordinary words don't seem potent enough. Confronted with the sublime: with the raw unfiltered beauty of nature, the splendor of the beacon of a full moon in the mid-winter forest on a night hike, for example, our most vivid adjectives fall short. We struggle to convey the luminosity, the abrupt silver opacity of the light, the quality of mystery, the energy that pools with dark radiance in pockets of shadow blueing behind trees. In these moments our language strains towards the poetic, because poetry is closer to a living language: a language of the Sacred. An experience can be so outwardly awe-inspiring, or so inwardly grand, that the best descriptors we can come up with are simply pale imitations.

Language can also fail us because the words in our arsenal seem sloppy and merely approximate–they do not allow us, with precision, to name the shape of the observed, the seen, or the felt. In our walk through the night forest we arrive now at the lake, across whose unmoving surface the moon's reflection lies clear as a road. And yet to say all this doesn't describe the elegance. Without the swedish word mangåta, we are left grasping, inarticulate.

MANGÅTA (Swedish) - NOUN - moon road

In these moments, we break the ordinary surface tension of our mother tongue like fish breaching– accidentally jumping out of water– for just a moment, realizing language is a medium, not reality.

These holes in language, these places where the map is incomplete, are known in English as lexical gaps, or lacuna(e), the latin word for lake. There is, for me, something hopeful, something vitalizing, about discovering a lacuna, a place where a word could (or even should) exist, and yet does not. There is some secret thrill I experience, like coming across a tiny altar on an unmarked trail, a sign someone else has stood here before, looking out or in, invoking naming, one of our defining arts. This makes me feel less alone every time it happens. It is subtly thrilling.

For twenty-eight years, I have been gathering untranslatable words. I started this project accidentally, in my late teens, at a time when I had dropped out of college, was struggling with depression, and had just begun to meditate. I kept having experiences that I didn't know how to locate on the map of the English language I had been brought up speaking. At first, there were qualities of attention that I couldn't describe with the words I had been taught. One of the early ones was 'equanimity'. Equanimity is the translation of Pali and Sanskrit words, Upekkha, which refers to keeping the mast of a ship upright in a storm. Equanimity, as it bears on attention, is the quality of keeping it fixed, unwavering, through the waves of emotion and experience that like to pull us around. Once I had located the proper word, this experience I was having as I learned to meditate became simpler for me to experience distinctly. Prior to the identification of the word, I had a hunch, an intuition, a vague sense of the attentional maneuver I was making. With the word came, suddenly, striking clarity.

Words are containers of culture. What a culture holds within the net of its language, as well as what is missing, tells us something about what it values, about what it is capable of perceiving. Words exist because people need them. From 'the metaverse' to 'beast mode' we are constantly accreting new language to describe our worlds. The Inuit have fifty words for snow because it is necessary to differentiate its typology with that degree of precision. I have felt, and feel, at many times in my life, enclosed by the modern world, enboxed by the English language, and discovering a word from another culture that voices some facet of the lived experience which cannot be spoken in English helps to crack the cage, helps let the moonlight stream through.

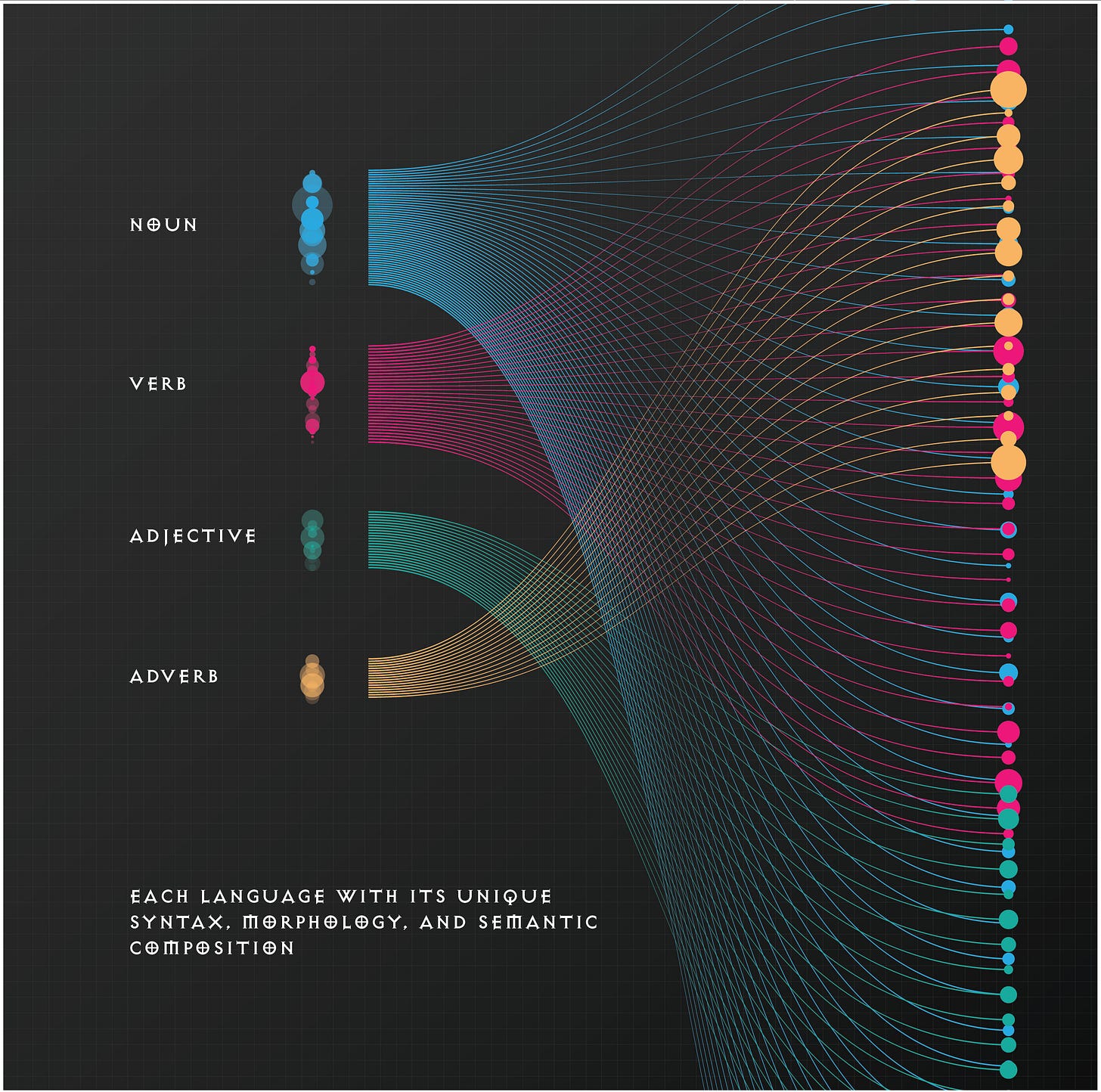

SYNTACTIC TOPOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

There is a deeper layer to this yet, beneath the individual words, which is that the English language is noun-based. Of the twentyfive hundred most commonly used English words, 1584 of them are nouns.

Of the twentyfive hundred most commonly used English words, 1584 of them are nouns.

We, in English, have been taught to perceive a world made of things. Yet not all languages are like this. I have the blessing of working with a number of Indigenous mentors, many of whom speak verb-based languages. My friend Tiokasin Ghosthorse, a speaker of the old Lakota language, describes Lakota as a non-mathematical quantum mechanical language of intuition. The mechanistic Newtonian world described by Sir Isaac several hundred years ago, with its anecdote of the gentleman watching an apple fall to the ground and conceptualizing gravity, was shown well over a hundred years ago to be an inadequate empirical explanation of the strangeness in which we find ourselves enmeshed, cosmologically speaking. In physics, the reality of a quantum worldview, with its attendant strangeness, its attendent nonduality, and non-locality, has supplanted, though we still don't live it, the Newtonian paradigm. And yet our language plods along, firmly entrenching our minds in a world of things that do not in fact exist.

The deeper problem with this, given the malleability of human consciousness, given the degree to which we are habit-forming creatures, is that a world of nouns tends to solidify us into a world of objects, whereas a world of verbs tends to vivify us within a world of relatedness. Nouns close, verbs open. Nouns contain, enbox. Verbs act, engage. Objects we stand outside of, at a distance. Relationships we exist within and between. Our linguistic inheritance is, therefore, one of separation, rather than one of relatedness. Our language domesticates reality, takes the stuffing out, entombs. And in this way, cracking the box of language becomes a more urgent existential project, because our inherited noun-based language is part of what builds humans who feel disconnected from, rather than entwined with, a living world. Breaking out of the box of dead language is part of the project of re/un/dis- covering the Indigenous Self.

This Substack is decidated to the missing words, the living words, that we require in order to more deeply name the relating of which we are a part, and that Empire has done its level best to denature.

It is part of our project of destorying (not a typo) empire.

Welcome to Keywords!

Hi - there is a typo:

In Swedish it's Mångata (not mongåta).

Måne (a moon) + gata (road/street).

En sträcka upplyst av månen så den bildar en strimma av ljus (ofta på vatten).

A line/reflection/band illuminated by the moon, creating a beam of light (often on water).

I love learning the phrase MANGÅTA. When I go to watch the Full Moon rise over the Bay, it is very hard to leave before (what I've called) the Moon Path appears, even when the wind is ripping. The missing words topic matters deeply to me, as I studied the Philosophy of Language, and the Philosophy of Creativity with a wonderful teacher while I was in Art School. Prioritizing interiority, indigeneity and relatedness matter greatly. Thank you for all you do.